Self-driving cars, facial recognition, and ChatGPT – these are just a few examples of the rapidly advancing tide of artificial intelligence. Will AI unlock unprecedented levels of human productivity and creativity, or will it reshape the world in a way that leaves many of us on the sidelines? Hear from an AI maximalist, an AI existentialist, and a religious scholar, then join the conversation.

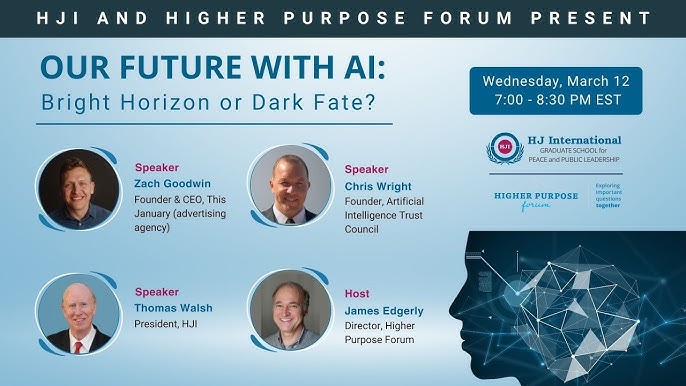

You will have the opportunity to hear from our speakers Mr. Zach Goodwin, Founder and CEO of This January, Mr. Chris Wright, Founder of Artificial Intelligence Trust Council, and Dr. Thomas Walsh, HJI President. Mr. James Edgerly, Director of Higher Purpose Forum, will be the host of the event.